The Stockholm and Rio Declarations are outputs of the first and second global environmental conferences, respectively, namely the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm, June 5-16, 1972, and the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro, June 3-14, 1992. Other policy or legal instruments that emerged from these conferences, such as the Action Plan for the Human Environment at Stockholm and Agenda 21 at Rio, are intimately linked to the two declarations, conceptually as well as politically. However, the declarations, in their own right, represent signal achievements. Adopted twenty years apart, they undeniably represent major milestones in the evolution of international environmental law, bracketing what has been called the “modern era” of international environmental law (Sand, pp. 33-35).

Stockholm represented a first taking stock of the global human impact on the environment, an attempt at forging a basic common outlook on how to address the challenge of preserving and enhancing the human environment. As a result, the Stockholm Declaration espouses mostly broad environmental policy goals and objectives rather than detailed normative positions. However, following Stockholm, global awareness of environmental issues increased dramatically, as did international environmental law-making proper. At the same time, the focus of international environmental activism progressively expanded beyond transboundary and global commons issues to media-specific and cross-sectoral regulation and the synthesizing of economic and development considerations in environmental decision-making. By the time of the Rio Conference, therefore, the task for the international community became one of systematizing and restating existing normative expectations regarding the environment, as well as of boldly positing the legal and political underpinnings of sustainable development. In this vein, UNCED was expected to craft an “Earth Charter”, a solemn declaration on legal rights and obligations bearing on environment and development, in the mold of the United Nations General Assembly’s 1982 World Charter for Nature (General Assembly resolution 37/7). Although the compromise text that emerged at Rio was not the lofty document originally envisaged, the Rio Declaration, which reaffirms and builds upon the Stockholm Declaration, has nevertheless proved to be a major environmental legal landmark.

Historical Background

In 1968-69, by resolutions 2398 (XXIII) and 2581 (XXIV), the General Assembly decided to convene, in 1972, a global conference in Stockholm, whose principal purpose was “to serve as a practical means to encourage, and to provide guidelines … to protect and improve the human environment and to remedy and prevent its impairment” (General Assembly resolution 2581 (XXVI). One of the essential conference objectives thus was a declaration on the human environment, a “document of basic principles,” whose basic idea originated with a proposal by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) that the conference draft a “Universal Declaration on the Protection and Preservation of the Human Environment”. Work on the declaration was taken up by the Conference’s Preparatory Committee in 1971, with the actual drafting of the text entrusted to an intergovernmental working group. Although there was general agreement that the declaration would not be couched in legally binding language, progress on the declaration was slow due to differences of opinion among States about the degree of specificity of the declaration’s principles and guidelines, about whether the declaration would “recognize the fundamental need of the individual for a satisfactory environment” (A/CONF.48/C.9), or whether and how it would list general principles elaborating States’ rights and obligations in respect of the environment. However, by January 1972, the working group managed to produce a draft Declaration, albeit one the group deemed in need of further work. The Preparatory Committee, however, loath to upset the compromise text’s “delicate balance”, refrained from any substantive review and forwarded the draft declaration consisting of a preamble and 23 principles to the Conference on the understanding that at Stockholm delegations would be free to reopen the text.

At Stockholm, at the request of China, a special working group reviewed the text anew. It reduced the text to 21 principles and drew up four new ones. In response to objections by Brazil, the working group deleted from the text, and referred to the General Assembly for further consideration, a draft principle on “prior information”. The Conference’s plenary in turn added to the declaration a provision on nuclear weapons as a new Principle 26. On 16 June 1972, the Conference adopted this document by acclamation and referred the text to the General Assembly. During the debates in the General Assembly’s Second Committee, several countries voiced reservations about a number of provisions but did not fundamentally challenge the declaration itself. This was true also of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics and its allies which had boycotted the Conference in Stockholm. In the end, the General Assembly “note[d] with satisfaction” the report of the Stockholm Conference, including the attached Declaration, by 112 votes to none, with 10 abstentions (General Assembly resolution 2994 (XXVII)). It also adopted resolution 2995 (XXVII) in which it affirmed implicitly a State’s obligation to provide prior information to other States for the purpose of avoiding significant harm beyond national jurisdiction and control. In resolution 2996 (XXVII), finally, the General Assembly clarified that none of its resolutions adopted at this session could affect Principles 21 and 22 of the Declaration bearing on the international responsibility of States in regard to the environment.

Following its adoption, in 1987, of the “Environmental Perspective to the Year 2000 and Beyond” (General Assembly resolution 42/186, Annex) – “a broad framework to guide national action and international co-operation [in respect of] environmentally sound development” - and responding to specific recommendations of the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED), the General Assembly, by resolution 44/228 of 22 December 1989, decided to convene UNCED and launch its preparatory committee process. The resolution specifically called upon the Conference to promote and further develop international environmental law, and to “examine … the feasibility of elaborating general rights and obligations of States, as appropriate, in the field of the environment”. Work on this objective, and on “incorporating such principles in an appropriate instrument/charter/statement/declaration, taking due account of the conclusions of all the regional preparatory conferences” (A/46/48), was assigned to Working Group III (WG-III) on legal and institutional issues whose mandate was expanded beyond States’ rights/obligations in the field of the environment, to include “development”, as well as the rights/obligations of other stakeholders (such as individuals, groups, women in development, and indigenous peoples). WG-III held its first substantive meeting during the Preparatory Committee’s third session in Geneva, in 1991. Actual drafting of the text of the proposed instrument, however, did not begin until the fourth and final meeting of the Preparatory Committee in New York, in March/April, 1992.

A proposal for an elaborate convention-style draft text for an “Earth Charter”, first advocated by a WCED legal expert group, did not win approval as it was specifically rejected by the Group of 77 developing countries (G-77 and China) as unbalanced, as emphasizing environment over development. The Working Group did settle instead on a format of a short declaration that would not connote a legally binding document. Still, negotiations on the text proved to be exceedingly difficult. Several weeks of the meeting were taken up by procedural maneuvering. In the end, a final text emerged only as a result of the forceful intervention of the chairman of the Preparatory Committee, Tommy Koh. The resulting document was referred to UNCED for further consideration and finalization as “the chairman’s personal text”. Despite threats by some countries to reopen the debate on the Declaration, the text as forwarded was adopted at Rio without change, although the United States (and others) offered interpretative statements thereby recording their “reservations” to, or views on, some of the Declaration’s principles. In resolution 47/190 of 22 December 1992 the General Assembly endorsed the Rio Declaration and urged that necessary action be taken to provide effective follow-up. Since then, the Declaration, whose application at national, regional and international levels has been the subject of a specific, detailed review at the General Assembly’s special session on Rio+5 in 1997, has served as a basic normative framework at subsequent global environmental gatherings, namely the World Summit on Sustainable Development in Johannesburg in 2002 and “Rio+20”, the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development in 2012.

Summary of Key Provisions and Their Present Legal Significance

a. General Observations

The Stockholm Declaration consists of a preamble featuring seven introductory proclamations and 26 principles; the Rio Declaration features a preamble and 27 principles. As diplomatic conference declarations, both instruments are formally not binding. However, both declarations include provisions which at the time of their adoption were either understood to already reflect customary international law or expected to shape future normative expectations. Moreover, the Rio Declaration, by expressly reaffirming and building upon the Stockholm Declaration, reinforces the normative significance of those concepts common to both instruments.

Both declarations evince a strongly human-centric approach. Whereas Rio Principle 1 unabashedly posits “human beings … at the centre of concerns for sustainable development”, the Stockholm Declaration — in Principles 1-2, 5 and several preambular paragraphs — postulates a corresponding instrumentalist approach to the environment. The United Nations Millennium Declaration 2000 (General Assembly resolution 55/2), also reflects an anthropocentric perspective on respecting nature. However, the two declarations’ emphasis contrasts with, e.g., the World Charter for Nature of 1982 (General Assembly resolution 37/7), and the Convention on Biological Diversity (preambular paragraph 1), whose principles of conservation are informed by the “intrinsic value” of every form of life regardless of its worth to human beings. Today, as our understanding of other life forms improves and scientists call for recognizing certain species, such as cetaceans, as deserving some of the same rights as humans, the two declarations’ anthropocentric focus looks somewhat dated.

At times Principle 1 of both the Stockholm and Rio Declarations has been mistaken to imply a “human right to the environment”. The Stockholm formulation does indeed refer to a human’s “fundamental right to … adequate conditions of life, in an environment of a quality that permits a life of dignity and well-being”. However, at the conference, various proposals for a direct and thus unambiguous reference to an environmental human right were rejected. The Rio Declaration is even less suggestive of such a right as it merely stipulates that human beings “are entitled to a healthy and productive life in harmony with nature”. Since then, the idea of a generic human right to an adequate or healthy environment, while taking root in some regional human rights systems, has failed to garner general international support, let alone become enshrined in any global human rights treaty. Indeed, recognition of a human right to a healthy environment is fraught with “difficult questions” as a 2011 study by the United Nations High Commissioner on Human Rights wryly notes.

As a basic UNCED theme, “sustainable development” — commonly understood as development that “meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs”(Our Common Future) — runs like an unbroken thread through the Rio Declaration. However, sustainable development is also a strong undercurrent in the Stockholm Declaration, even though the WCED was not to coin the concept until several years after Stockholm. For example, Principles 1-4 acknowledge the need for restraint on natural resource use, consistent with the carrying capacity of the earth, for the benefit of present and future generations. The Rio Declaration expands on the sustainable development theme and significantly advances the concept by, as discussed below, laying down a host of relevant substantive and procedural environmental legal markers. Nevertheless, to this day the actual operationalization of the concept has remained a challenge. In this vein, on the eve of “Rio+20”, United Nations Secretary-General Ban felt compelled to reiterate the urgent need for “sustainable development goals with clear and measurable targets and indicators.”

b. The Prevention of Environmental Harm

Probably the most significant provision common to the two declarations relates to the prevention of environmental harm. In identical language, the second part of both Stockholm Principle 21 and Rio Principle 2 establishes a State’s responsibility to ensure that activities within its activity or control do not cause damage to the environment of other States or to areas beyond national jurisdiction or control. This obligation is balanced by the declarations’ recognition, in the first part of the respective principles, of a State’s sovereign right to “exploit” its natural resources according to its “environmental” (Stockholm) and “environmental and developmental” policies (Rio). While at Stockholm some countries still questioned the customary legal nature of the obligation concerned, today there is no doubt that this obligation is part of general international law. Thus in its Advisory Opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons first, and again more recently in the Case concerning Pulp Mills on the River Uruguay, the International Court of Justice expressly endorsed the obligation as a rule of international customary law. Moreover, the Pulp Mills decision clearly confirms that the State’s obligation of prevention is one of due diligence.

c. The Right to Development in an Environmental Context

Both at Stockholm and at Rio, characterization of the relationship between environment and development was one of the most sensitive challenges facing the respective conference. Initial ecology-oriented drafts circulated by western industrialized countries failed to get traction as developing countries successfully reinserted a developmental perspective in the final versions of the two declarations. Thus, after affirming that “both aspects of man’s environment, the natural and the man-made, are essential to his well-being” (preambular paragraph 1), Principle 8 of the Stockholm Declaration axiomatically labels “economic and social development” as essential. Rio Principle 3, using even stronger normative language, emphasizes that the “right to development must be fulfilled so as to equitably meet developmental and environmental needs of present and future generations”. Although the United States joined the consensus on the Declaration, in a separate statement it reiterated its opposition to development as a right. The international legal status of the “right to development” has remained controversial even though, post-Rio, the concept has attracted significant support, e.g. through endorsements in the 1993 Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action, and the Millennium Declaration. At any rate, there is no denying that the Rio formulation has had a strong impact on the international political-legal discourse and is frequently invoked as a counterweight to environmental conservation and protection objectives. Today, economic development, social development and environmental protection are deemed the “interdependent and mutually reinforcing pillars” of sustainable development (Johannesburg Plan of Action, para.5).

d. Precautionary Action

One of several of the Rio Declaration Principles that does not have a counterpart in the Stockholm Declaration is Principle 15, which provides that “the precautionary approach shall be widely applied by States according to their capabilities:” Whenever there are threats of serious or irreversible damage, a lack of full scientific certainty shall not excuse States from taking cost-effective measures to prevent environmental degradation. At Rio, a European initiative proposing the inclusion of precautionary action as a “principle” failed to gain support. Today, the concept is widely reflected in international practice, although there exists no single authoritative definition of either its contents or scope. This has prompted some States, including the United States, to question its status as both a “principle of international law” and a fortiori a rule of customary international law (World Trade Organization, European Communities – Measures Affecting the Approval and Marketing of Biotech Products, paras.7.80-7.83). However, in its 2011 Advisory Opinion, the Seabed Chamber of the International Tribunal of the Law of the Sea takes note of “a trend towards making this approach part of customary international law”, thereby lending its voice to a growing chorus that recognizes “precaution” as an established international legal principle, if not a rule of customary international law.

e. “Common but Differentiated Responsibilities”

While today the concept of “common but differentiated responsibilities” (“CBDR”) is accepted as a cornerstone of the sustainable development paradigm, it is also one of the more challenging normative statements to be found in the Rio Declaration. The second sentence of Principle 7 provides: “In view of the different contributions to global environmental degradations, States have common but differentiated responsibilities”. Ever since its adoption, its exact implications have been a matter of controversy. Specifically, taken at face value the formula seems to imply a causal relationship between environmental degradation and degree of responsibility. However, “differential responsibilities” has been considered also a function of “capability” reflective of a state’s development status. Unlike the essentially contemporaneously drafted provision in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which refers to States’ “common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities” (Article 3, para.1, emphasis added), the second sentence of Principle 7 omits any reference to capabilities. A separate sentence in Principle 7 does acknowledge the relevance of capabilities. But it does so in relation to developed countries’ special responsibility regarding sustainable development on account of “the technologies and financial resources they command”. Principle 7 indirectly, then, links developing country status to “responsibilities”. What remains unclear, at any rate, is whether “CBRD” implies that developing country status in and of itself entails a potential diminution of environmental legal obligations beyond what a contextually determined due diligence standard would indicate as appropriate for the particular country concerned. Certainly, both the Stockholm and Rio Declarations (Principle 23 and Principle 11, respectively) expressly recognize the relevance of different national developmental and environmental contexts for environmental standards and policies purposes. However, developing country status per se does not warrant a lowering of normative expectations. At Rio, the United States stated for the record that it “does not accept any interpretation of Principle 7 that would imply a recognition or acceptance by the United States of … any diminution of the responsibilities of developing countries under international law”. The United States delegation offered the same “clarification” in respect of various references to “CBDR” in the Plan of Implementation of the World Summit on Sustainable Development in 2002. Consistent with this view, the 2011 International Tribunal of the Law of the Sea Advisory Opinion, in construing the scope of a State’s international environmental obligations, refused to ascribe a special legal significance to developing country status and instead affirmed that “what counts in a specific situation is the level of … capability available to a given State…”.

f. Procedural Safeguards

Principles 13-15 and 17-18 of the Stockholm Declaration — rather modestly — emphasize the need for environmental and development planning. The absence of any reference in the Declaration to a State’s duty to inform a potentially affected other state of a risk of significant transboundary environmental effects was due to the working group on the Declaration’s inability to reach agreement on such a provision. However, the working group did agree on forwarding the matter to the General Assembly which, as noted, endorsed such notification as part of States’ duty to cooperate in the field of the environment. By contrast, the Rio Declaration unequivocally and in mandatory language calls upon States to assess, and to inform and consult with potentially affected other States, whenever there is a risk of significantly harmful effects on the environment: Principle 17 calls for environmental impact assessment; Principle 18 for emergency notification and Principle 19 for (routine) notification and consultation. At the time of the Rio Conference, and perhaps for a short while thereafter, it might have been permissible to question whether the contents of all three principles corresponded to international customary legal obligations. However, today given a consistently supportive international practice and other evidence, including the International Law Commission’s draft articles on Prevention of Transboundary Harm from Hazardous Activities, any such doubts would be misplaced.

g. Public Participation

Principle 10 of the Rio Declaration posits that “[e]nvironmental issues are best handled with the participation of all concerned citizens, at the relevant level”. It then calls upon States to ensure that each individual has access to information, public participation in decision-making and justice in environmental matters. Although Principle 10 has some antecedents in, for example, the work of the Organization of Economic Co-operation and Development, it nevertheless represents a trail blazer, laying down for the first time, at a global level, a concept that is critical both to effective environmental management and democratic governance. Since then, international community expectations, as reflected notably in the Convention on Access to Information, Public Participation in Decision-Making and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters (Aarhus Convention), the 2010 UNEP Guidelines for the Development of National Legislation on Access to Information, Public Participation and Access to Justice in Environmental Matters and various resolutions of international organizations and conferences, have coalesced to the point where the normative provisions of Principle 10 must be deemed legally binding. While the actual state of their realization domestically may be still be a matter of concern—implementation by States of their Principle 10 commitments is specifically being reviewed within the context of Rio+20—today the rights of access to information, public participation, and access to justice arguably represent established human rights.

h. The Interface of Trade And Environment

In Principle 12 of the Declaration, the Rio Conference sought to address one of the controversial issues of the day, the interrelationship between international trade and environmental conservation and protection. After exhorting States to avoid trade policy measures for environmental purposes as “a means of arbitrary or unjustifiable discrimination or a disguised restriction on international trade” — language that closely follows the chapeau of Article XX of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) — Principle 12 criticizes States’ extra-jurisdictional unilateral action: “Unilateral actions to deal with environmental challenges outside the jurisdiction of the importing country should be avoided”. This provision traces its origin to a proposal by Mexico and the European Community both of which had been recent targets of United States environment-related trade measures. Responding to the adoption of Principle 12, the United States offered an interpretative statement that asserted that in certain circumstances trade measures could be effective and appropriate means of addressing environmental concerns outside national jurisdiction. This U.S. position has now been fully vindicated. As the World Trade Organization Appellate Body first acknowledged in the Shrimp-Turtle cases, unilateral trade measures to address extraterritorial environmental problems may indeed be a “common aspect” of measures in restraint of international trade exceptionally authorized by Article XX of the GATT.

i. Indigenous Peoples

Rio Principle 22 emphasizes the “vital role of indigenous people and their communities and other local communities” in the conservation and sustainable management of the environment given their knowledge and traditional practices. It then recommends that States “recognize and duly support their identity, culture and interests and enable their effective participation in the achievement of sustainable development”. Even at the time of its drafting this was a somewhat modest statement, considering that in the case of indigenous peoples, cultural identity and protection of the environment are inextricably intertwined. Thus some international legal instruments such as the International Labour Organization Convention (No. 169) concerning Indigenous and Tribal Peoples in Independent Countries of 1989 and the Convention on Biological Diversity, which was opened for signature at Rio, already specifically recognized and protected this relationship. Since Rio, indigenous peoples’ special religious, cultural, indeed existential links with lands traditionally owned, occupied or used have been further clarified and given enhanced protection in a series of landmark decisions by human rights tribunals as well as in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (General Assembly resolution 61/295).

j. Women in Development

The Rio Declaration was the very first international instrument to explicitly recognize that the empowerment of women and, specifically, their ability to effectively participate in their countries’ economic and social processes, is an essential condition for sustainable development. Principle 20 of the Rio Declaration calls attention to women’s “vital role in environmental management and development” and the consequent need for “their full participation.” It recognizes the fact that women’s livelihood, in particular in developing countries, often will be especially sensitive to environmental degradation. Unsurprisingly, this “women in development” perspective has been strongly endorsed in other international legal instruments, such as the preambles of the Convention on Biological Diversity or the Desertification Convention, and in resolutions of various international conferences. In short, as a United Nations Development Programme website puts it, gender equality and women’s empowerment represent not only fundamental human rights issues, but “a pathway to achieving the Millennium Development Goals and sustainable development.” However, as the calls for “sustainability, equity and gender equality” at Rio+20 seem to underline, much work appears still to be necessary before the Principle 20 objectives will truly be met.

k. Environmental Liability and Compensation

Finally, both the Stockholm and the Rio Declarations call for the further development of the law bearing on environmental liability and compensation. Whereas Stockholm Principle 22 refers to international law only, the corresponding Rio Principle 13 refers to both national and international law. Notwithstanding these clear mandates, States have tended to shy away from addressing the matter head-on or comprehensively, preferring instead to establish so-called private law regimes which focus on private actors’ liability, while mostly excluding consideration of States’ accountability. Recent developments, however, when taken together, can provide a basic frame of reference for issues related to environmental liability and compensation, be that at national or international level. These developments include, in particular, the work of the International Law Commission, especially its draft Principles on Allocation of Loss in the Case of Transboundary Harm Arising out of Hazardous Activities; and the 2010 UNEP Guidelines for the Development of Domestic Legislation on Liability, Response Action and Compensation for Damage Caused by Activities Dangerous to the Environment. In this vein, therefore, it might be argued that today the expectations of legislative progress generated by the Stockholm and Rio Declarations have finally come to be realized, at least in large part.

This Introductory Note was written in May 2012.Select Related Materials

A. Legal Instruments

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade, 30 October 1947, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 55, p. 187.

Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment, in Report of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, UN Doc.A/CONF.48/14, at 2 and Corr.1 (1972).

Convention on Biological Diversity, 5 June 1992, United Nations, Treaty Series, vol. 1760, p. 79.

Rio Declaration on Environment and Development, in Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, UN Doc. A/CONF.151/26 (Vol. I), 12 August 1992, Annex I.

Draft Articles on Prevention of Transboundary Harm from Hazardous Activities in Report of the International Law Commission, Official Records of the General Assembly, Fifty-sixth Session, Supplement No. 10 (A/56/10).

Draft principles on the allocation of loss in the case of transboundary harm arising out of hazardous activities in Report of the International Law Commission, Official Records of the General Assembly, Sixty-first Session, Supplement No. 10 (A/61/10).

B. Other Documents

Report of the Preparatory Committee for the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, Second Session 1971 (A/CONF.48/PC.9).

General Assembly resolution 2995 (XXVII) of 15 December 1972 (Co-operation between States in the field of the environment).

General Assembly resolution 2996 (XXVII) of 15 December 1972 (International responsibility of States in regard to the environment).

Expert Group on Environmental Law of the World Commission on Environment and Development, Environmental Protection and Sustainable Development: Legal Principles and Recommendations (1987).

Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future, 4 August 1987 (A/42/427, Annex).

General Assembly resolution 42/186 of 11 December 1987 (Environmental Perspective to the Year 2000 and Beyond).

General Assembly resolution 43/196 of 20 December 1988 (United Nations Conference on Environment and Development).

General Assembly resolution 44/228 of 22 December 1989 (United Nations Conference on Environment and Development).

Report of the Preparatory Committee for the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development, 1991 (A/46/48).

General Assembly resolution 47/190 of 22 December 1992 (Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development).

Vienna Declaration and Programme of Action of 12 July 1993 (A/CONF.157/23).

Rio Declaration on Environment and Development: Application and Implementation, Report of the Secretary-General, U.N. Doc. E/CN.17/1997/8, 10 February 1997.

World Trade Organization, United States – Import Prohibition of Certain Shrimp and Shrimp Products – Recourse to Article 21.5 of the DSU by Malaysia, Doc. WT/DS58/AB/RW (22 October 2001).

Report of the World Summit on Sustainable Development, 2002 (A/CONF.199/20), Resolution 2, Annex (Plan of Implementation of the World Summit on Sustainable Development).

World Trade Organization, European Communities – Measures Affecting the Approval and Marketing of Biotech Products, Reports of the Panel, 29 September 2006 (WT/DS291/R, WT/DS292/R WT/DS293/R).

General Assembly resolution 61/295 of 13 September 2007 (United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples).

C. Articles-Books

Bekhechi, “Le droit international àl’épreuve du développement durable: Quelquesréflexionsà propos de la Déclaration de Rio surl’environnementet le développement,” Hague Yearbook of International Law 59 (1993).

Beyerlin, “Rio-Konferenz 1992: BeginneinerneuenglobalenUmweltordnung,” 54 ZeitschriftfürausländischesöffentlichesRecht und Völkerrecht 124 (1994).

Brunnée, “The Stockholm Declaration and the Structure and Processes of International Environmental Law”, T. Dorman, ed., The Future of Ocean Regime Building: Essays in Tribute to Douglas M. Johnston (2008).

Handl, “Sustainable Development: General Rules vs. Specific Obligations”, W. Lang, ed., Sustainable Development and International Law 35 (1995).

Kiss, “The Rio Declaration on Environment and Development”, L. Campiglio, L. Pineschi, D. Siniscalco & T. Treves, eds., The Environment after Rio: International Law and Economics 55 (1994).

Kiss and Sicault, “La Conférence des Nations Unies sur l’environnement”, Annuaire Français de Droit International 603 (1972).

Kovar, “A Short Guide to the Rio Declaration”, 4 Colorado Journal of International Environmental Law & Policy 119 (1993).

Lal Panjabi, “From Stockholm to Rio: Comparison of the Declaratory Principles of International Environmental Law”, 21 Denver Journal International Law & Policy 215 (1993).

Mann, “The Rio Declaration”, 86 Proceedings ASIL 406 (1992).

Marchisio, “Gliatti di Rio nel diritto internazionale”, 75 Rivista di dirittointernazionale 581 (1992).

Ntambirweki, “The Developing Countries in the Evolution of an International Environmental Law”, 14 Hastings International & Comparative Law Journal 905 (1991).

Pallemaerts, “La conference de Rio: Grandeur oudécadence du droit international de l’environnement?”, 28 Revue belge de droit international 175 (1995).

Robinson, “Problems of Definition and Scope”, J. Hargrove, ed., Law, Institutions, and the Global Environment 44 (1972).

Sand, “The Evolution of International Environmental Law”, D. Bodansky, J. Brunnée & E. Hey, eds., The Oxford Handbook of International Environmental Law 29 (2007).

Sohn, “The Stockholm Declaration on the Human Environment”, 14 Harvard International Law Journal 423 (1973).

Declaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment Rio Declaration on Environment and DevelopmentDeclaration of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment

Following a proposal of the Government of Sweden, formalized in a letter dated 20 May 1968, the Economic and Social Council decided to place the question of convening an International Conference on the Problems of the Human Environment on the agenda of its mid-1968 session (letter dated 20 May 1968 from the Permanent Representative of Sweden addressed to the Secretary-General of the United Nations, E/4466/Add.1). The explanatory memorandum attached to the letter stated that the changes in the natural surroundings, brought about by man, had become an urgent problem for developed as well as developing countries, and that these problems could only be solved through international co-operation. The Swedish Government proposed to convene a conference under the auspices of the United Nations, to work on a solution for the problems of human environment.

To assist the Economic and Social Council in its consideration of the question, the Secretary-General prepared a report outlining the work and programmes of the various organizations of the United Nations family, relevant to the problems of the human environment (E/4553). During its mid-1968 session, a draft resolution entitled “Question of convening an international conference on the problems of human environment” was submitted to the Economic and Social Council (E/L.1226). After revision, the Economic and Social Council adopted resolution 1346 (XLV) of 30 July 1968, by which it recommended that the General Assembly include the item entitled “The problems of human environment” in the agenda of its twenty-third session and consider the desirability of convening a conference on problems of the human environment.

At its twenty-third session, the General Assembly, in plenary, considered the item entitled “The problems of the human environment” on 3 December 1968. It had before it the report of the Economic and Social Council (A/7203), a note by the Secretary-General (A/7291), as well as a draft resolution sponsored by fifty-five Member States (A/L.553 and Add.1-4). The General Assembly adopted resolution 2398 (XXIII) of 3 December 1968, in which it decided to convene a United Nations Conference on the Human Environment and requested the Secretary-General to submit a report concerning, inter alia, the nature, scope and progress of work being done in the field of human environment, the main problems in this area, and the possible methods of preparing the Conference.

At its forty-seventh session in 1969, the Economic and Social Council considered the report of the Secretary-General entitled “Problems of the human environment” which had been prepared in response to General Assembly resolution 2398 (XXIII) (E/4667). A draft resolution sponsored by seventeen Member States was introduced and adopted as resolution 1448 (XLVII) of 6 August 1969 by the Economic and Social Council. The resolution recommended that a Preparatory Committee be established, a small conference secretariat be set up, and the Secretary-General be entrusted with overall responsibility of organizing the Conference (A/7603).

At the twenty-fourth session of the General Assembly in 1969, the item was allocated to the Second Committee, which had before it a note prepared by the Secretary-General (A/7707), including the Economic and Social Council resolution, and recommending the adoption of a resolution on this matter. On 12 November 1969, the Second Committee approved, by acclamation, a draft resolution introduced by Chile, Ethiopia, Finland, India, Iran, Jamaica, Mexico, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, Sweden and Yugoslavia (A/C.2/L.1069 and Add.1). Upon the recommendation of the Second Committee (A/7866), the General Assembly unanimously adopted resolution 2581 (XXIV) on 15 December 1969, which established the Preparatory Committee for the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment and requested the Secretary-General to submit a progress report through the Economic and Social Council to the General Assembly for its twenty-fifth session.

The Preparatory Committee held its first session from 10 to 20 March 1970 and submitted its report to the General Assembly (A/CONF.48/PC/6).

On 19 June 1970, in response to the request of the General Assembly, the Secretary-General submitted a progress report to the Economic and Social Council (E/4828). The Economic and Social Council took note of the progress report by its resolution 1536 (XLIX) on 27 July 1970.

At its twenty-fifth session, the General Assembly considered the item “United Nations Conference on the Human Environment” and adopted resolution 2657 (XXV) of 7 December 1970 on this matter.

The Preparatory Committee held its second session from 8 to 19 February 1971 (A/CONF.48/PC/9), and its third session from 13 to 24 September 1971 (A/CONF.48/PC/13). During these sessions, the Preparatory Committee established an inter-governmental working group to prepare a draft declaration on the human environment and four other working groups to work on issues of marine pollution, soils, surveillance and conservation, respectively.

At its twenty-sixth session, the Second Committee of the General Assembly considered the item entitled “United Nations Conference on Human Environment” (A/8577). Serving as a basis for discussion was a report by the Secretary-General on the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (A/8509). At the same session, the General Assembly adopted, on the recommendation of the Second Committee, resolution 2849 (XXVI) of 20 December 1971, by which it set forth conditions for the action plan and the action proposals that were to be submitted to the Conference. On the same day, the General Assembly also adopted resolution 2850 (XXVI) in which it, inter alia, approved the provisional agenda and draft rules of procedure for the Conference as submitted by the Preparatory Committee, and requested the Secretary-General to conclude the preparations for the Conference and to circulate in advance of the Conference a draft declaration on the human environment.

The fourth and final session of the Preparatory Committee was held from 6 to 10 March 1972. The Preparatory Committee agreed upon a draft preamble and principles of a declaration on the human environment, submitted by an inter-governmental working group (A/CONF.48/PC/16), and further agreed to forward the draft declaration to the Conference for consideration (A/CONF.48/PC/17).

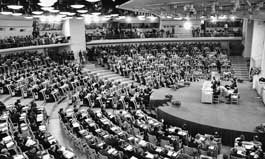

The United Nations Conference on the Human Environment was held in Stockholm, Sweden, from 5 to 16 June 1972. The Conference was attended by representatives of 113 Member States of the United Nations, as well as members of the specialized agencies of the United Nations. The Conference documents drew upon a large number of papers received from Governments as well as inter-governmental and non-governmental organizations, including 86 national reports on environmental problems (Report of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, Stockholm, 5 to 16 June 1972, A/CONF.48/14).

The Conference established a Working Group on the Declaration on the Human Environment as well as three main committees to study the six substantive items on its agenda, namely: planning and management of human settlements for environmental quality; educational, informational, social and cultural aspects of environmental quality; environmental aspects of natural resources management; development and environment; identification and control of pollutants of broad international significance; and international organizational implications of action proposals. On 16 June 1972, after consideration and discussion of the reports of the main committees and of the Working Group, the Conference adopted by acclamation, subject to observations and reservations, the Declaration on the Human Environment, which consisted of a preamble and 26 principles. The Declaration was based on the text of the draft declaration submitted by the Preparatory Committee, as revised and amended by the Working Group on the Declaration on the Human Environment and by the Conference in plenary. The Conference also adopted 109 recommendations for environmental action at the international level. The report of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment (A/CONF.48/14 and Corr.1), which contained the Declaration, was transmitted by the Secretary-General to the Economic and Social Council and to the General Assembly (E/5217 and A/8783, respectively).

The Economic and Social Council took note of the report of the Conference by a decision of 17 October 1972 (E/5209/Add.1). At its twenty-seventh session, the General Assembly, on the recommendation of the Second Committee, adopted resolution 2994 (XXVII) on 15 December 1972, by which it noted with satisfaction the report of the Conference and drew the attention of Governments to the Declaration. It also designated 5 June as World Environment Day.

Rio Declaration on Environment and Development

At its thirty-fifth session, in 1980, the General Assembly examined the agenda item entitled “International cooperation in the field of the environment” in plenary. The Assembly adopted resolution 35/74, entitled “International cooperation in the field of the environment” on 5 December 1980 in plenary on the recommendation of the Second Committee. The Assembly, inter alia, took note of the report of the Governing Council of the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP), which had held its eighth session from 16 to 29 April 1980, in which the Council examined the report of the high-level group of experts on the interrelationships between population, resources, environment and development. The Assembly also decided to convene, in 1982, a session of a special character of the Governing Council to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, held in Stockholm.

The Governing Council of UNEP adopted a resolution at its session of special character, held from 10 to 18 May 1982 (A/37/25), in which it recommended to the General Assembly the establishment of a special commission to propose long-term environmental strategies for achieving sustainable development to the year 2000 and beyond (the “Environmental Perspective”).

At its thirty-seventh session, the General Assembly adopted resolution 37/219 of 20 December 1982 in plenary on the recommendation of the Second Committee, requesting the Governing Council of UNEP at its eleventh session to make concrete recommendations to the General Assembly, through the Economic and Social Council, on the modalities for preparing the Environmental Perspective. Pursuant to this resolution, the Governing Council of UNEP adopted decision 11/3 at its eleventh session, on 23 May 1983, regarding the process of preparation of the Environmental Perspective and annexed a draft resolution for consideration by the General Assembly on the creation of an intergovernmental inter-sessional preparatory committee, which was to report to the Economic and Social Council, and of a special commission to propose long-term environmental strategies for achieving sustainable development.

In 1983, the Economic and Social Council took note of this decision and recommended to the General Assembly the adoption of the draft resolution (E/DEC/1983/168). At the General Assembly’s thirty-eighth session in the same year, the Assembly adopted resolution 38/161 of 19 December in plenary on the recommendation of the Second Committee, by which it approved the decision to establish an intergovernmental inter-sessional preparatory committee. It also suggested that the special commission, when established, report on the environment and the global problématique to the year 2000 and beyond, including proposed strategies for sustainable development, within two years of its establishment, and set out the terms of reference for the special commission.

The Intergovernmental Inter-sessional Preparatory Committee held its first session on 28 and 29 May 1984. The Governing Council of UNEP adopted the Preparatory Committee’s first set of recommendations by decision 12/1 of 29 May 1984, and the Governing Council additionally noted the progress made in the establishment of the Special Commission (Report of the Governing Council of the United Nations Environment Programme on the work of its twelfth session to the General Assembly, 16 to 29 May 1984, A/39/25). The Special Commission, which had adopted the name the World Commission on Environment and Development in 1984, began its work in May 1984.

At its fortieth session, in 1985, the General Assembly adopted resolution 40/200 of 17 December in plenary on the recommendation of the Second Committee, in which it, inter alia, took note of the work done by the World Commission, and of the work by the Intergovernmental Inter-sessional Preparatory Committee in the preparation of their reports.

In March 1987, the World Commission on Environment and Development issued the report “Our Common Future” (A/42/427), in which it made a formal recommendation that relevant legal principles should be consolidated and extended in a new charter to guide State behaviour in the transition to sustainable development, and it submitted a set of proposed legal principles for the purpose of drafting a universal declaration.

At its fourteenth session, in 1987, the Governing Council of UNEP, by it decision 14/13, adopted the Environmental Perspective to the Year 2000 and Beyond, prepared by the Intergovernmental Inter-sessional Preparatory Committee, and recommended for adoption by the General Assembly a draft resolution on incorporating an environmental perspective. At the same session, the Governing Council also adopted decision 14/14, entitled “Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development”, and, inter alia, decided to transmit the Commission’s report to the General Assembly, for its consideration and adoption by Member States, together with a draft resolution annexed to the decision, welcoming the findings of the World Commission and, inter alia, calling upon Governments, as well as the governing bodies of the organs, organizations and programmes in the United Nations system, to ensure that their activities contribute to sustainable development.

At its forty-second session, the General Assembly adopted resolution 42/187 of 11 December 1987 in plenary on the recommendation of the Second Committee, in which it welcomed the report of the World Commission on Environment and Development and decided to transmit the report to Governments and governing bodies of the organs, organizations, and programmes of the United Nations. It also requested the Secretary-General to submit to the General Assembly a progress report on the implementation of the resolution and a consolidated report on the same subject. The General Assembly further invited the Governing Council of UNEP to provide comments on matters concerning progress on sustainable development to the Economic and Social Council and General Assembly, and invited Governments, in co-operation with UNEP and, as appropriate, intergovernmental organizations, to support and engage in follow-up activities, such as conferences at national, regional and global levels.

In May 1988, the Secretary-General submitted to the General Assembly, through the Economic and Social Council, a progress report (A/43/353 - E/1988/71) on the implementation of General Assembly resolution 42/187. The report set out the actions taken by Governments, governing bodies and other intergovernmental organizations to implement policies on sustainable development.

During the forty-third session of the General Assembly, in 1988, a draft resolution was introduced by Finland in the Second Committee, on behalf of Canada, Denmark, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway and Sweden, which proposed that a United Nations Conference on Environment and Development be convened in 1992 (A/C.2/43/L.36). On 23 November 1988, the Second Committee had before it a revised version of the draft resolution (A/C.2/43/L.36/Rev.1). On 5 December 1988, the Committee adopted draft resolution A/C.2/43/L.36/Rev.2, as orally revised, and recommended its adoption to the General Assembly. The General Assembly thus adopted resolution 43/196 of 20 December 1988, where it decided to consider at its forty-fourth session the question of convening such a conference no later than 1992. The Assembly also took note of the progress report of the Secretary-General on the implementation of resolution 42/187. The Assembly requested the Secretary-General, with the assistance of the Executive Director of UNEP, to obtain and submit views on the objectives, content and scope of the conference to the General Assembly at its forty-fourth session, through the Economic and Social Council. It also invited the Governing Council of UNEP to submit its views in the same manner.

In response to the request of the General Assembly, the Secretary-General submitted a report, containing the views of Governments, organs, organizations and programmes of the United Nations, intergovernmental organizations and non-governmental organizations on the convening of the conference on environment and development. Several responses cited the importance and timeliness of such a conference, and there was a general agreement that an intergovernmental preparatory committee would be required (A/44/256 and Corr.1 & Add.1 & 2).

On 25 May 1989, the Governing Council of UNEP adopted decision 15/3, in which it decided to recommend that the General Assembly, when taking a decision on the scope, title, venue and date of the proposed United Nations conference on environment, consider a number of elements that were attached as an annex to the Governing Council’s decision. The decision was then transmitted to the General Assembly for consideration by the Economic and Social Council in resolution 1989/87 of 26 July 1989.

On 18 December 1989, at the forty-fourth session of the General Assembly, the Second Committee approved a draft resolution introduced by its Chairman (A/C.2/44/L.86) and recommended it to the General Assembly for adoption. On 22 December 1989, upon this recommendation, the General Assembly adopted resolution 44/228, by which it decided to convene a United Nations Conference on Environment and Development in Brazil and to establish a Preparatory Committee for the Conference which was to prepare draft decisions for the Conference for consideration and adoption. The Assembly also requested the Secretary-General to prepare a report for the organizational session of the Preparatory Committee, containing recommendations on an adequate preparatory process. The Assembly also decided to include in the provisional agenda of its forty-fifth and forty-sixth sessions an item entitled “United Nations Conference on Environment and Development”.

The Preparatory Committee held its organizational and first session from 5 to 16 March and 6 to 31 August 1990 during which it established two working groups to provide guidance to the preparatory process (Reports of the Preparatory Committee for the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development to the General Assembly, A/44/48 and A/45/46). On 21 December 1990, the General Assembly adopted resolution 45/211 in which it took note of the report of the Preparatory Committee and decided that the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development shall take place at Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, from 1 to 12 June 1992.

The second session of the Preparatory Committee was held from 18 March to 5 April 1991. During the session, the Preparatory Committee established Working Group III, which was tasked with, inter alia, examining the feasibility of elaborating principles on general rights and obligations of States and regional economic integration organizations in the fields of environment and development, and considering the feasibility of incorporating such principles in an appropriate instrument, charter, statement or declaration (Report of the Preparatory Committee for the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development to the General Assembly, A/46/48).

At the third session of the Preparatory Committee, held from 12 August to 4 September 1991, the Secretariat of the Conference prepared an annotated check-list of principles on general rights and obligations to be considered at the Conference (A/CONF.151/PC/78). A draft proposal was also introduced by Ghana on behalf of the Group of 77, entitled “Rio de Janeiro Charter/Declaration on Environment and Development” (A/CONF.151/PC/WG.III/L.6). The Chairman of Working Group III subsequently compiled all proposals submitted by delegations in a consolidated draft (A/CONF.151/PC/WG.III/L.8/Rev.1), which was taken as the basis for discussion at the fourth session of the Preparatory Committee (Report of the Preparatory Committee for the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development to the General Assembly, A/46/48).

During its forty-sixth session, in 1991, the General Assembly considered the reports of the Preparatory Committee and, on 19 December 1991, adopted resolution 46/168 on the recommendation of the Second Committee, in which it called for the full implementation of resolution 44/228. The Assembly set out the entities that were to be invited to attend the Conference, and endorsed the decisions taken by the Preparatory Committee in their second and third sessions. The Assembly also decided to include in the provisional agenda of its forty-seventh session an item entitled “Report of the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development”.

The Preparatory Committee held its fourth and final session from 2 March to 3 April 1992. The Chairman of the Preparatory Committee introduced draft principles proposed by him, entitled “Rio Declaration on Environment and Development” (A/CONF.151/PC/WG.III/L.33/Rev.1). The Preparatory Committee adopted decision 4/10 in which it decided to transmit the proposal to the Conference for further consideration (A/CONF.151/PC/128).

The United Nations Conference on Environment and Development was held from 3 to 14 June 1992 in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. On 10 June, the Main Committee of the Conference reviewed the proposal submitted by the Chairman of the Preparatory Committee on the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development (A/CONF.151/5). Upon the proposal of its own Chairman, the Main Committee approved, by acclamation, the Rio Declaration and recommended it to the Conference for adoption (A/CONF.151/5/Rev.1). At its 19th plenary meeting, on 14 June, the Conference had before it a draft resolution entitled “Adoption of texts on environment and development”, with the Rio Declaration as recommended by the Main Committee attached as an annex, sponsored by the delegation of Brazil (A/CONF.151/L.4/Rev.1). The Conference adopted the draft resolution to this effect by which it accordingly adopted the Rio Declaration (A/CONF.151/26/Rev.1).

At its forty-seventh session, the General Assembly had before it the report of the Conference (A/CONF.151/26/Rev.1). Upon the recommendation of the Second Committee, the General Assembly adopted resolution 47/190 of 22 December 1992, in which it endorsed the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development and urged Governments and organs, organizations and programmes of the United Nations system to take the necessary action to give effective follow-up to the Rio Declaration.

Selected preparatory documents

(in chronological order)